Part I. Delineating the object of our study

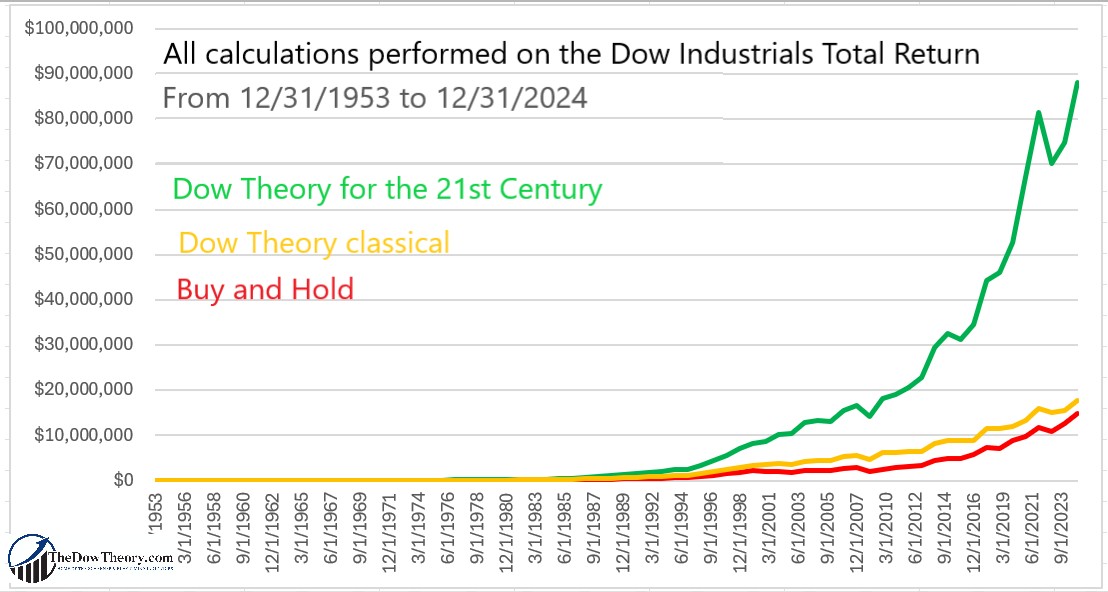

This study was completed in 2013, but its conclusions remain unchanged to this day. The chart below, which epitomizes the saying “a picture is worth a thousand words,” displays how the Schannep’s Dow Theory (The Dow Theory for the 21st Century, DT21C) outperforms the classical Dow Theory and Buy and Hold as of December 2024.

It is no secret that this blogger truly yours has always passionately defended Schannep’s Dow Theory “flavor.” For the uninitiated, it suffices to say that the Dow Theory is not monolithic; hence, different variations of a common theme coexist in hopefully peaceful harmony. More about the different Dow Theory flavors here.

Classical Dow Theorists are very adamant about any changes to the Dow Theory as was expounded by Rhea, and, in my opinion, due to a lack of understanding of Schannep’s flavor tend to dismiss any improvement of the Dow Theory as heretical or defective.

However, I have always contended that Schannep’s rules make full a priori and empirical sense. To learn more about Schannep’s flavor of the Dow Theory and Rhea, please go here.

To put it succinctly, three different ways of investing coexist under the name “Dow Theory,“, namely:

- One based on the secular trend, lasting for 10 or more years. Positions taken along the secular trend can last even a decade, and good values (i.e, high dividend yield) are paramount to establish a long position. At the risk of oversimplifying, this is the way Charles Dow (partially) and Schaefer advocated.

- One based on spotting cyclical bull and bear markets irrespective of value considerations. While the writings of Charles Dow contain hints as to this kind of investing, Dow’s understudy Hamilton, and finally Rhea are the ones that really developed the rules pertaining to this specific kind of trend following. Most market practitioners agree that the Rhea version of the Dow Theory is the “classic” one.

- Schannep, on the footsteps of Rhea, produced a more updated and responsive Dow Theory “flavor.”, which is essentially Rhea’s Dow Theory with steroids. This is the Dow Theory “flavor” which is followed by this blogger, truly yours.

Well, actually, Schannep’s goes beyond tweaking the Rhea/classic Dow Theory. While the backbone of Schannep’s timing system is the Dow Theory (as improved by him), he avails himself of other “tools” to strengthen his market calls. Thus, Schannep’s timing system is made of:

- First of all, the Dow Theory. I’d confidently say that 90% of his buy and sell signals are based on the Dow Theory (which is pure trend following).

- 5% or so of the buy and sell signals is Schannep’s bull and bear market definition, namely a decline of -16% for a bear market and a rally of +19% for a bull market. While many Dow Theory buy and sell signals overlap Schannep’s bull and bear market definition, in some rare instances the market makes such powerful movements before a Dow Theory signal is flashed (here you can read more about Schannep’s bull and bear market definition). In any instance, taking buy and sell signals based on previous advances or declines is, without any shade of doubt, trend following. Schannep’s website, “thedowtheory.com,” contains a list of bull and bear markets according to this definition.

- The remainder is a buy-only signal, the so-called “capitulation.” When markets experience a dramatic decline (as measured by Schannep’s proprietary indicators), investors are advised to exceptionally deviate from trend following and, instead, bet on a trend reversal. In other words, when the market is severely oversold, buy and expect a new bull market soon. Of course, this is not trend following but, rather, mean reversal trading, which is in the antipodes conceptually of trend following. However, Schannep’s capitulation indicator (more information can be found here) has served him well in the past.

Therefore, it is very important to make a rigorous comparison of the “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory with Schannep’s. After all, we shouldn’t get blinded by Schannep’s outperformance of ca. 2% versus the “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory. If such outperformance were achieved with deeper drawdowns or with an extremely high turnover (and its attendant commissions and slippage), then we would be better advised to stick to the traditional Dow Theory, which is a great timing system in and of itself. Thus, I set out to study Schannep’s performance and transactions from all possible angles. I will leave no stone unturned.

However, I want to make an apple to apples comparison. If I am going to compare Schannep’s Dow Theory flavor with the “classical Rhea”, I feel I cannot take the full corpus of Schannep’s tools, since some of these tools, despite their effectiveness, have nothing to do with the Dow Theory.

Accordingly, before I proceed to compare Schannep’s Dow Theory flavor with the “Rhea/classical” one, I am going to trim Schannep’s system somewhat.

First, I will eliminate the “capitulation” rule. As I mentioned earlier, the capitulation rule suggests opening a long position when the market is severely oversold. It is catching the proverbial “falling knife.” Thus, this indicator, although effective, has been ignored in the calculations I have made. An oscillator by its nature (mean reversal) is in the antipodes of any trend following method (among which is the Dow Theory).

On the other hand, I will integrate Schannep’s definition of bull and bear markets (+19% and -16% movements, respectively) because this is pure trend following. This is the essence of any breakout, momentum-based system, and, hence, it bodes well with the Dow Theory. In any instance, there were only one buy and one sell signal based upon this rule during the time period studied (which spans almost 60 years) out of a total of 31 round trades.

Curiously enough, my “trimming” of Schannep’s sophisticated machinery didn’t result in a significant deterioration of performance. This attests to the robustness of Schannep’s Dow Theory rules. In other words, Schannep’s Dow Theory rules don’t need the crutch of other indicators to excel and outperform the Rhea/Classical Dow Theory. This is not to downplay the importance of capitulation, because it is the icing on the cake, adding value and performance by smoothing signals and enabling the transition from a fully invested to a partially invested position and vice versa. However, since the “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory record doesn’t contain “Capitulation“, the proper way to compare Schannep’s interpretation of the Dow Theory is by reducing his system to just the Dow Theory, and the bull/bear market definition of +19 and -16% market movement, respectively.

Bearing in mind the preceding considerations, I am confident that I have conducted a real “apples to apples” comparison. I have compared two trend-following systems of a very similar nature.

In the coming posts, we will compare both “flavors” from the following angles:

- Total performance.

- Trade duration.

- Time in the market.

- Profit factor.

- Percentage of winning trades.

- Average winning trade.

- Average losing trade.

- Largest losing trade.

- Win to lose ratio.

- Profit factor.

- Total performance in secular bull markets

- Total performance in secular bear markets.

- And much more…

Well, now is the time to put an end to this lengthy post. Those thirsting for “data” should wait for the next post, which follows below. However, since this is a serious attempt to analyse both Schannep’s and the “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory, it was necessary to clarify our premises and the object of our study. To begin with, it suffices to say that Schannep’s Dow Theory “flavor” excels on all counts. My conviction regarding the importance of Schannep’s contribution to the art of market timing has been further cemented after having performed this in-depth study.

Part II. Overall performance figures

Today we will continue our comparison of the “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory versus the Schannep’s version thereof. Our previous post, which you can find here, set out the premises of our study, as it is important to do a real “apple to apples” comparison.

Today, we will begin to evaluate the transactions taken in pursuance of Schannep’s Dow Theory, and we will compare them with the transactions taken in accordance with the “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory.

Our study spans from 1954 to 2013. We chose 1954 as our starting date, as Schannep’s flavor dates back to this year. You can find Schannep’s Dow Theory record here.

With no more preambles let’s get started.

Schannep versus Traditional Dow Theory vital statistics

Total number of transactions (trades) taken:

Schannep:32

Classical:24

Comment:

We observe that Schannep’s Dow Theory resulted in ca. 1/3 more transactions than the classical Dow Theory.

This higher figure is in itself neutral. It can be beneficial if more frequent trading results in decreased risk (drawdowns) and increased profits, or it can be detrimental if it fails to achieve that goal.

However, I can make two observations:

- In spite of being ca. 1/3 more reactive to market conditions, Schannep’s version has nothing to do with short term trading. 32 transactions in almost 60 years bear no resemblance to short-term trading, and hence we can infer that commissions and slippage should not plague Schannep’s performance.

- My investor and short-term trader experience has proven to me beyond any shade of doubt that the only way to avoid deep drawdowns when a bear market hits is by increasing the number of trades (i.e., by getting in and out quickly). Of course, overtrading can decimate your trading account. Thus, it is necessary to strike a balance between overtrading and overstaying a falling market. I find that the Schannep’s version of the Dow Theory strikes a very good balance between inaction and frantic activity.

Average duration of each transaction:

Schannep: 479 days.

Traditional: 629 days.

Let’s take a look at the median duration:

Schannep: 357 days.

Traditional: 403 days.

We can see that, on average, transactions taken in pursuance of Schannep’s rules last approximately 23.8% less than those taken according to the traditional Dow Theory.

Once again, a shorter life span for each transaction isn’t necessarily good or evil, in itself. Thus, even though each transaction has a shorter life-span, we also know that there are more transactions when following Schannep.

So we must be patient and wait for more data, such as:

Average gain in each transaction

Schannep: 22.07%

Traditional: 26.36%

Here I can see Schannep’s detractors shouting loudly: “You see Schannep’s Dow Theory severely underperforms the classical Dow Theory.”

I’d say to them: “Not so fast.”

A more accurate measure is average gain per year. Thus, I’d prefer to make 10% per annum rather than make 30% in ten years. Thus, we must normalize returns over time.

Since Schannep’s transactions last significantly less (almost 24% less) than those taken according to the traditional Dow Theory, annualized performance would be:

Schannep: 16.8%

Traditional: 15.29%

So things now start to look much better for Schannep. This statistic is telling us that Schannep’s signals “extract” more profits from the market in less time, or, in other words, given equal time fully invested in the market, Schannep’s rules manage to make more money. This is a clear measure of efficiency. Or in plain English: Schannep’s rules do a better job at separating a true signal from noise.

Inquisitive readers should be thinking right now:

“This statistic is a little bit misleading, as we really don’t know if there have been enough signals so that overall performance in the last 59 years has really been superior to that of the classical Dow Theory. What good is a more “efficient” signal if we don’t get enough of them or, worse yet, its life-span is so meager than in real life, there is not enough time to build up meaningful profits.”

I will address this criticism.

If we take base=100 in 1954 for both Dow Theory “flavors”, such 100 would have grown into:

Growth of 100 USD since 1954

Schannep:14,973

Traditional: 8,756

We can see that, despite having shorter trades, Schannep’s rules generated enough trades to make meaningful profits. Thus, Schannep’s claim that his “flavor” outperforms the classical Dow Theory by ca. 2% annual, is a correct one.

Total time in the market

Schannep:70.6

Traditional: 70.8%

Now it gets even more interesting. Even though Schannep’s transactions last less than those taken as per the classical Dow Theory rules, the total amount of time spent on the market is almost the same. This implies:

- a) That Schannep’s rules compensate shorter duration for each trade with more trades.

- b) Since total profit is much higher, the time spent on the market is best used, which implies it is better at “timing” the market.

Winning transactions (trades) versus losing trades

Schannep: 23 winners/9 losers (71.8% winners)

Traditional: 17 winners/7 losers (70.8% winners)

So we see that both Dow Theory flavors have a very similar percentage of winning trades. A high batting average, while not necessary for high profits (as low percentage systems can score good profits provided the average winning trade greatly exceeds the average losing trade), is important in real life because: (a) it increases confidence in the system; (b) drawdowns tend to be reduced as there is less likelihood of a long string of losses. Any short-term trader worth his salt knows what I mean right now. Here, both “flavors” excel.

….

Well, little by little, we are deepening our understanding of Schannep’s Dow Theory, and, more importantly, why it is objectively better than the “classical” Dow Theory (which, in itself, is also an excellent timing system). Furthermore, the figures we are examining do not do full justice to Schannep’s Dow Theory. We will further explore this assertion when we close this saga of posts.

Part III Overall performance figures

Let’s continue with our analysis of the Schannep’s version of the Dow Theory versus the “Rhea/classical” one.

Please note that my analysis does not discriminate between secular bull and bear markets. The study of both Dow Theory “flavors” under bull and bear secular market conditions will be conducted at a later stage, providing us with further insights into what to expect from both Dow Theory “flavors.”

Schannep versus Traditional Dow Theory vital statistics

Average winning trade

Schannep: 33.42%

Classical: 40.45%

As I explained in the previous post in this series, performance percentages in themselves is misleading. We have to normalize across time. In other words, what really interests us as investors is how much money each Dow Theory flavor can make given the same amount of time.

To this end, I derived the following figures:

Average total time in the market (winning trades)

Schannep: 621.26 days

Classical: 828.35 days

Once again, we see that the transactions taken as per Schannep’s Dow Theory tend to last slightly less than those taken in pursuance of the classical Dow Theory. If we calculate the median duration, we obtain similar results (425 versus 645 days).

If we translate the average duration of winning trades into years, we obtain:

Schannep: 1.70 years

Classical: 2.27 years

If we divide the average percentage gain by the total time spent on the market in order to achieve such a gain, we obtain the normalized profit figure. Thus, the annualized performance for winning trades for each Dow Theory “flavor” would amount to:

Schannep: 19.63%

Traditional: 17.82%

This statistic is telling us that Schannep’s winning trades “extract” more profits from the market in less time, or, in other words, given equal time fully invested in the market, Schannep’s rules manage to make more money.

Well, now let’s turn our eyes to the losing trades. We learn more from observing defeat than from rejoicing in victory.

Average Losing trade

Schannep: -6.48%

Classical: -7.85%

When it comes to losing money, Schannep’s Dow Theory (The Dow Theory for the 21st Century) does a better job at protecting one’s capital. Here you begin to see why the relative “restiveness” (more trades generated) by Schannep’s flavor, comes to the investor’s help when the going gets tough. There is a lot of talk about letting profits run, which is true; however, to cut losses short, it is necessary to have a system that doesn’t overstay markets when the trend reverses course. Schannep’s slightly shorter duration of trades comes in handy when it comes to adverse market conditions.

Averages do not do full justice to Schannep’s Dow Theory, so we will further study the universe of losing trades.

Let’s take a look at the two largest losing trades.

| Year | Schannep | Classical | |

| 1st Losing Trade | 2008 | -10.45 | -19.33 |

| 2nd Losing Trade | 1970 | -8.33 | -10.62 |

Well, the difference between the two “flavors” is astounding. The implications are obvious: When a bear market sets in, Schannep’s Dow Theory gets you out of trouble in the blink of an eye. It is not the same in real life to lose -10.45% as to lose -19.33%. Real investors and traders will certainly agree with me.

Therefore, what I wrote concerning the efficacy of the “classical” Dow Theory in containing losses becomes even truer when dealing with Schannep’s Dow Theory:

We also observe that the Dow Theory avoided catastrophic losses in all instances. Even 2008s -19.33% loss compares favorable with the ca. -55% meltdown the S&P500 experienced. In all other instances, losses are few and well contained. Thus, Dow Theory acts as an excellent capital protector. The best offense (returns) is a good defense (contained losses). As I wrote here when evaluating year-end returns:

“Investors get blinded by performance. However, in real life, the investor is killed by drawdowns. A 15% average performance is worth nothing if, somewhere along the road, there is going to be a drawdown of -50%. Buy and hold is nice in theory, and it may work provided the investor has deep pockets (staying power) and psychological fortitude. However, in real life, very few investors possess both attributes simultaneously. Thus, the publicized return figures of many investing strategies are not attainable in real life because the investor cannot endure the drawdowns. If the average retiree needs to draw 4% off his capital annually (and this is a very realistic and even modest assumption), a drawdown of 50% in any given year, will force him to draw 8% if he wants to keep his expenditures intact. Of course, he can cut with expenses, but as we well know, this is not an easy feat. Even if the retiree manages to reduce expenditures by 25%, this implies a withdrawal of 6% while being in the midst of the drawdown. As a result, total equity would be reduced by 50%+6%, thereby remaining only 44% of his original capital. A draw down of such magnitude is akin to a black hole. It is very difficult to escape from it. In most instances, the retiree will exhaust all of his capital. Game over for him!”

If you couple these findings with the fact that winning trades managed to make more profits given the same amount of time in the market, or as we examined in our last post, that overall Schannep’s version makes more money than the “Rhea/classical Dow Theory, it is clear that slightly increasing the number of trades has nothing to do with “overtrading” or churning one’s equities account, but, rather, being able to spot changes of trend and get out of trouble as soon as possible. I repeat ad nauseam that the only way to avoid killing drawdowns when a bear market sets in is by increasing the frequency of trades. There is no way around this market truism.

Let’s further analyze the losing trades from another perspective. Hitherto, we have focused on the average losing trade. Let’s look at the standard deviation of losing trades. The lower the standard deviation, the better, as it indicates a lower probability of “extreme” surprises occurring in the future. While nothing is carved in stone, and anything may happen in the future, I certainly prefer to stick to a system that has shown stability in losses under adverse market conditions.

Standard Deviation of losing trades

Schannep: 2.67%

Traditional: 5.84%

So, as you can see, the likelihood of scoring big losses is much higher (more than double standard deviation) when following the classical Dow Theory.

The analysis I have just made of losing trades has profound implications. Schannep’s Dow Theory isn’t just a way to “outperform” the classical Dow Theory (and by implication buy and hold); it is an excellent devise to cut losses short (and to avoid unpleasant surprises in the “untested” and “out of sample” future) under challenging markets. We will further expand on this remarkable feature of Schannep’s Dow Theory when we break down our analysis into secular bull or bear markets. Some astounding conclusions will emerge.

If, as I contend, Schannep’s Dow Theory does a better job at cutting losses short, we should expect the average duration of losing trades to be shorter than those of the “classical” Dow Theory. If Schannep gets out of trouble quickly, trades that get sour should have a shorter duration. Here you have the answer:

Average duration of losing trades

Schannep:123.00 days

Classical: 145.14 days

If we calculate the “median” instead of the average, we obtain even more telling results:

Median duration of losing trades

Schannep: 81 days

Classical: 147 days

No matter how we measure it, losing trades under Schannep’s Dow Theory have shorter durations. This is obviously a positive, and suggests, looking forward to the unknown future, the risk of getting caught in a bad trade is smaller for those following Schannep’s rules.

As a side note, I’d like to mention that the work of L.A. Little on the duration of bear markets clearly supports my contention that the earlier one gets out of trouble, the better. Mr. Little, in his well-researched book “Trend Trading Set-ups” provides compelling empirical evidence that losing trades start losing money early on, which proves the market adage “cut your losses short” right.

Win-to-lose ratio

I calculated this ratio by summing up the total percentage points made in winning trades and dividing this figure by the summation of total percentage points lost in losing trades. Here you have the results:

Schannep:5.15

Classical: 5.14

Here Schannep’s Dow Theory manages to slightly beat the “classical” version of the Dow Theory. However, both ratios are excellent. We should not forget that the “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory is an excellent timing device on its own right.

Profit factor

Profit factor is the quotient of total points gained divided by total points lost. More about the importance of a healthy profit factor here.

From 1954 to 2013, we got the following profit factors:

Schannep:13.17

Classical: 12.5

Once again, both “flavors” manage to sport a wonderful profit factor. Please note that in the trading world, any profit factor larger than 2 is considered outstanding. However, the profit factor only tells part of the story. The volatility of losses and the likelihood of a very big one is something not to be underestimated. As I have shown in this post, while both “flavors” manage to avoid big losses, Schannep’s version clearly does an even better job.

……

My next post will focus on studying both Dow Theory flavors under secular bull markets. Figures such as the average trade duration and average profit clearly vary depending on the market’s secular condition. This is something to consider for the real market practitioner in order to adjust expectations and better assess the reward-to-risk ratio of each prospective trade. Thus, when being immersed in a secular bear market, it should not come as a surprise that the transactions taken in pursuance of the Dow Theory (of any “flavor” whatsoever) fall short of expectations. The problem does not lie with the Dow Theory but with our expectations. If we break down the historical record into secular bull and bear markets, we will have a more accurate yardstick against which to measure our expected and realized performance. To the best of my knowledge, this is groundbreaking work that has not been performed yet. So readers of this Dow Theory blog, stay tuned!

Part IV. Performance comparison under secular bull markets.

Until now, this series “Face off: Schannep versus ‘classical’eory has focused on comparing Schannep’s and “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory irrespective of the secular condition of the market. In Part I, we set out the premises of our study (so that we conduct an apples-to-apples comparison). In parts II and III, we provided a wealth of data concerning both Dow Theory “flavors”. However, the results of our analysis did not differentiate between secular bull and bear markets.

And the secular condition of the market does matter. Positions taken under secular bull markets tend to last longer and be more profitable than trades taken under secular bear markets. By secular market, I mean a market condition that spans many years, which goes beyond the 1-3-year duration of cyclical bull and bear markets. Dow Theorist Schaeffer wrote that secular markets could last up to 14 years. While I am reluctant to put a limit on the duration of secular bull and bear markets, one thing is certain: they last longer than cyclical bull and bear markets and clearly influence the outcomes of the trades taken along cyclical bull and bear markets. However, determining secular bull/bear market conditions is not an easy feat in real time. It appears simple when examining charts ex post facto (after the fact). Unlike spotting cyclical bull and bear markets, which, under Dow Theory, is done with the exclusive aid of price patterns, determining the secular condition of the market is not an easy feat in real time, since it entails determining value. And “value” determination is far from easy.

As I have written some days ago:

“While classifying secular bull and bear markets is always subjective, there are some guidelines like “q” “PER” or dividend yield, which may come in handy. In a nutshell, secular bull markets start when stocks are very good values. While determining value is always elusive (and this accounts for my being interested in cyclical bull and bear markets with an average duration of less than 2 years), we need a frame of reference. Personally, I am skeptical as to PER and dividend yield for reasons to be explained in a future post on this Dow Theory blog. However, having read, and, more importantly, digested, Smithers and Wright book “Valuing Wall Street” (which you can buy here), I personally feel that the “q” ratio a quite dependable measure of the cheapness or dearness of a market on a secular basis.”

The longer the life span of a trade, the more important fundamental and value considerations are. If you are day-trading, earnings, business prospects, etc, play no role in forecasting the stock’s price in the next five minutes. Technical considerations (and significant randomness) are the overriding factors. However, if you lengthen your time horizon to, say, 10 years, fundamental and value-based considerations will prevail, and technical analysis will pale in comparison.

Dow Theorist Schaeffer, and to some extent, Richard Russell, advocate for investing along the secular trend. Rhea, Schannep, and this blogger truly yours feel more comfortable investing during the cyclical bull and bear markets that occur within the secular trend, reasons for which will be given in a future post on this Dow Theory blog. Since, by definition, cyclical bull and bear markets have a shorter duration than secular trends (let’s put it at 1-3 years), the technical condition of the market plays a greater role in determining the outcome of any given trade. Accordingly, the Dow Theory rules are a valuable tool (in my opinion, the best one) for determining the trend on a cyclical basis (1-3 years). Nonetheless, the secular condition of the market, as a distant but powerful tide, affects the profitability of the cyclical bull markets. A secular bull market puts the very long term tide in your favor. This is why it is essential to determine the secular trend of the market, even if one is not interested in investing alongside it.

All in all, both Schannep’s and the “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory generate trades that exploit cyclical bull markets. Neither “flavor” attempts to invest along the secular trend. However, the secular trend affects the outcome of the trades taken along cyclical bull markets, and, hence, it makes sense to, albeit tentatively, be able to determine the secular condition of the market. The secular condition of the market will be “head” or “tail” wind, and, thus, it is not to be neglected.

While defining “secular” bull and bear markets is subjective, I have tabulated the following periods:

From 1954 to 1967: SECULAR BULL

From 1968 to 1981: SECULAR BEAR

From 1982 to 2000: SECULAR BULL

From Mid 2000 to 2011: SECULAR BEAR.

After this lengthy but necessary introduction, let’s begin with our analysis of transactions conducted during secular bull markets.

Schannep versus Traditional Dow Theory vital statistics (secular bull markets)

Total number of transactions (trades) taken:

Schannep:11

Classical:10

Commentary:

When secular market conditions are propitious, Schannep’s Dow Theory flashes almost the same number of signals than the “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory. So much for the accusation of Schannep’s Dow Theory being too restive. From this figure, we can deduct that the slightly higher activity of Schannep’s Dow Theory (more trades) takes place when most needed: When a secular bear market results in many aborted cyclical bull markets. When there is headwind, more transactions are the antidote against being caught in a monstrous drawdown. More about this when we analyze Schannep’s performance under secular bear markets. However, when there is tailwind (secular bull market), Schannep’s Dow Theory is as calm as the “classical” Dow Theory.

Average duration of each transaction:

Schannep: 864 days.

Traditional: 856 days.

Commentary

This is astounding. If you have been following this “face-off” series, you know that when the secular condition of the market is not taken into account, the average trade duration for Schannep’s Dow Theory was ca. 24% shorter than the average trade duration for the “classical” Dow Theory.

Now we see that when we zero in on secular bull markets, the average duration of each transaction is actually longer (albeit marginally) for Schannep’s Dow Theory than for the classical. From this finding, we derive three conclusions:

- The myth of Schannep’s Dow Theory being too restive is just that: a myth. When there is a tailwind (secular bull market), Schannep’s Dow Theory excels at sticking with the prevailing trend, and accordingly, its trades manage to outlast those taken in pursuance of the “classical” Dow Theory.

- Schannep’s Dow Theory is better in sync with cyclical bull markets. Longer trade duration implies that more “meat” from each cyclical bull market is extracted by Schannep’s Dow Theory.

- Longer trade duration also tells us that Schannep’s Dow Theory is better at timing the entry and exit points, as it stays invested for a longer time in the market.

Average gain in each transaction

Schannep: 53.37%

Traditional: 51.27%

Comment:

Once again, Schannep’s Dow Theory beats the classical one on this score. However, to be fully sure of the superiority of Schannep’s Dow Theory, it is necessary that we annualize performance so that we account for Schannep’s longer average trade duration. If we normalize, we obtain the following figures:

Schannep: 22.55%

Traditional: 21.85%

Comment:

Please mind that this figure merely divides the average gain in each transaction by the average time in each transaction. We can see that, given an equal amount of time (i.e., 1 year), Schannep’s Dow Theory manages to extract more profit from the market than the Dow Theory.

While ca. 0.7% annual outperformance doesn’t seem much, we have to bear in mind that, once we capitalize, we see that Schannep’s competitive edge builds up significant profits over time:

If we take base=100 in 1954 for both Dow Theory “flavors”, such 100 would have grown into:

Growth of 100 USD since 1954

Schannep:5594

Traditional: 3301

Please note that this capitalization refers only to the 10 transactions for the classical Dow Theory and 11 for Schannep’s, which were made during secular bull markets. Thus, this is not the total performance of either Schannep’s or the “classic” Dow Theory (as the gains made during secular bear markets are not included). It is merely an indication of what to expect during secular bull markets. However, the figures above clearly show that Schannep’s does a much better job at accumulating profits when conditions are favorable.

Total time in the market (total days invested during secular bull markets)

Schannep:9502 days

Traditional: 8563 days

Comment:

This statistic shows that Schannep’s Dow Theory manages to “stick” to the cyclical bullish trend longer than the traditional Dow Theory. Since, as we have seen, profits are larger for Schannep’s Dow Theory we conclude that Schannep’s Dow Theory is more efficient at selecting the right trends. More time on the market also suggests that Schannep’s Dow Theory tends to get us early aboard (and earlier than the “classical” one). Furthermore, since I know that Schannep’s Dow Theory tends to exit a trade earlier than the classical Dow Theory, we have to conclude that the time spent on the market is well spent.

This assertion is proved if we divide the total percentage points gained by the total time spent in the market.

Total percentage points gained (non-capitalized summation):

Schannep:587.07

Traditional: 512.74

Total time in the market:

Schannep:9502 days

Traditional: 8563 days

Percentage points gained per day:

Schannep:0.0617%

Traditional: 0.0598%

Thus, we can see that given an equal amount of time, Schannep’s Dow Theory was ca. 3.17% more efficient than the “classical Dow Theory.” This leads me to conclude that Schannep’s Dow Theory is a better market timing device than the classical Dow Theory.

Winning transactions (trades) versus losing trades

Schannep: 11 winners/0 losers (100% winners)

Traditional: 9 winners/1 losers (90% winners)

Comment:

While “past performance is no guarantee for future performance,” it appears that under secular bull market conditions, Schannep’s Dow Theory is better attuned to the market’s “pulse.”

Since we are analyzing transactions under secular bull markets, the only loser incurred by the “classical” Dow Theory is of minor importance (-5.60% in 1990). However, it is noteworthy that the equivalent trade taken in pursuance of Schannep’s rules, resulted in a modest gain of +2.25% proving, once again, that under challenging market conditions, Schannep’s flavor does a much better job at protecting one’s equity. It is not the same to lose -5,60% than to win +2.25%.

Profit factor

Profit factor is the quotient of total points gained divided by total points lost. More about the importance of a healthy profit factor here.

From 1954 to 2013, we get the following profit factors:

Schannep: Infinite (no hype)

Classical: 92.55

Well, this comparative study of both Dow Theory flavors under secular bull markets is drawing to an end.

Schannep’s Dow Theory outperformance is kind of an accomplishment, since during secular bull markets it is very difficult to beat buy and hold or anything closely resembling it (as the “classical” Dow Theory, which theoretically is less prone to trading and hence is more similar to buy and hold). This is a testament to the net superiority of Schannep’s Dow Theory.

Even though Schannep’s outperformance under secular bull markets is certainly good news, I must confess that I am more interested in comparing both Dow Theory flavors when the going gets tough, namely, under secular bear markets. Rule number one of investing is not to lose money; and money is lost, and in spades, during secular bear markets. Thus, instead of getting greedy and rejoicing at Schannep’s outperformance during secular bull markets (when even buy-and-hold investors can make a nice return without the threat of a significant drawdown), I am more interested in seeing how both Dow Theory flavors fare under adverse market conditions (i.e., secular bear markets). It is under market stress when I expect to see Schannep’s Dow Theory to really shine; being the outperformance under secular bull markets just an appetizer.

Part V. Performance comparison under secular bear markets

Today, we will close this saga by comparing Schannep’s Dow Theory and the classical Dow Theory during secular bear markets.

You can find here the full explanation as to what constitutes a “secular” bull or bear market. This is important stuff as the secular condition of the market clearly influences the outcome of the trades taken in pursuance of the Dow Theory (be it “Schannep’s” of “classical”).

Average Trade duration during bear markets

Classical: 1.19 years (436 days)

Schannep: 0.7 years (283 days)

Some people I have in mind would immediately jump on Schannep and say:

“You see…transactions following Schannep’s Dow Theory last too short, as the ‘classical’ Dow Theory signals last significantly longer. This proves Schannep’s Dow Theory is not so effective.”

Well, this is a very bad analysis. Very bad and superficial analysis, indeed.

During secular bear markets, the “gravitational force” intensifies, making the market prone to false breakouts, and even successful cyclical bull markets tend to be smaller in extent (and duration, as there is a direct correlation between profits and the duration of the trade). Under these adverse circumstances overstaying the market is not advisable. The investor should be ready to leave as soon as there is any hint of danger. This is why transactions taken as per Schannep’s Dow Theory flavor last less during secular bear markets. We are ready to turn on a dime.

Furthermore, the duration of each transaction is not so important, what really matters is how much money we make. So now let’s look at the average gain following each Dow Theory “flavor”:

Average gain made in each transaction during secular bear markets.

Classical: 6.52%

Schannep: 5.46%

Now the crowd gets more vociferous against Schannep:

“You see, your trades last too short, you don’t give your trades enough time to build profits. Can’t you see that the classical Dow Theory has a larger average profit!”

Well, once again wrong, plain wrong, since we have to look at the total number of transactions during bear markets. From 1954 to 2013 there have been the following number of transactions:

Total number of transactions during secular bear markets:

Classical: 13

Schannep: 20

Thus, Schannep’s Dow Theory, the DT21C, signaled more buy and sell signals than the classical Dow Theory during secular bear markets. This is neutral. It remains to be seen whether so much “activity” was noise or resulted in more profits to the investor than the less restive classical Dow Theory.

To this end, we have to look at the total percentage points gained during secular bear markets by each Dow Theory “flavor”:

Total percentage points gained during secular bear markets:

Classical: 84.77

Schannep: 109.10

So, surprise, surprise! Schannep’s Dow Theory manages to extract more profits from the market during secular bear markets. This implies that:

a) Schannep’s Dow Theory is much more effective during secular bear markets than the “Rhea/Classical” Dow Theory in determining when to get “in” and, more importantly, when to get “out”. If market conditions do not warrant a long, strong trend, so be it; Schannep’s Dow Theory will not be remiss in terminating a trade, even if this means a shorter average trend duration than the classical Dow Theory.

By being more attuned to market conditions, Schannep’s Dow Theory flavor was able to generate more profits for investors during secular bear markets. Schannep’s made 28.7% more profits than the “Rhea/classical” Dow Theory during such fateful periods.

b) If we divide the average percentage made in each transaction by the total average time, we see that Schannep’s Dow Theory, in spite of trades that last on average 35% less than “classical” ones, manages to “extract” from the market more money per time unit. If we divide the average trade by the average duration of each trade, we can see the average profit extracted from the market each day. Let’s do the math:

Classical:

6.52% (Avg Trade) /436.54 (Avg time) = 0.01493687% per day.

Schannep:

5.46% (Avg Trade) /283.45 (Avg time) = 0.01924533 % per day.

Thus, Schannep’s Dow Theory manages to make 28.86% more than the classical Dow Theory on average per day.

Of course, such figures are not carved in stone and we don’t know what the future has in store for us. However, I’ll tend to side with the Dow Theory flavor that shows a greater degree of responsiveness; especially when the market is more likely to cause devastating losses.

The best offense is a good defense, so let’s take a look at the losing trades.

Average Losing Trade

Classical: 7.19%

Schannep: 6.48%

We can see that Schannep’s Dow Theory manages to lose less when the market refuses to cooperate.

One could argue that averages are misleading, so we need to examine the individual trades. Thus, a lower average percentage loss might be concealing a monster loss. To this end, let’s take a look at the two largest losses incurred by each Dow Theory flavor.

Largest loss (Schannep): -10.45% (Jan 30, 2009)

Largest loss (Classical): -19.33% (Sep 29, 2008)

So the most significant loss under the Rhea/Classical Dow Theory almost doubles the loss suffered by Schannep’s Dow Theory.

Let’s take a look now at the second-largest loss:

Second largest loss (Schannep): -8.33% (Jan 26, 1970)

Second largest loss (Classical): -10.62% (Jan 26, 1970)

Hence, while we can make no assurances about the future, it seems that Schannep’s Dow Theory does a remarkably better job at “cutting your losses short”. Furthermore, as we have amply seen during this saga of posts, Schannep’s Dow Theory reduces risk (losses) without compromising returns (actually, returns are increased by Schannep’s Dow Theory).

Conclusions:

This post is coming to a close. Each market practitioner should derive his own conclusions. Personally, I find that the evidence weighs overwhelmingly in favor of Schannep’s Dow Theory. I am not implying the the “Rhea/Classical” Dow Theory is flawed, far from it. I still consider the classical Dow Theory as an excellent market timing device. However, I feel Schannep’s “improvements” are far from being “ego-improvements”; they are real, well substantiated, and empirically shown to work.

While it may be argued that “past performance is no guarantee for future performance”, I’d say that the very structure of Schannep’s Dow Theory is likely to continue outperforming the “classical” Dow Theory in the future. By design Schannep’s Dow Theory is more responsive (i.e. detects earlier the onset of a new trend) because:

- It uses three indices (it includes the S&P), instead of just two, whereas it requires just two indices to confirm.

- The definition of secondary reaction (which is vital to determine breakout points, which in turn, define primary and bear market signals) is “shortened” as, 10 days, or even less, is enough to qualify a movement as a secondary reaction.

- In the same vein, by doing away with the 1/3 to 2/3 retracement rule (which is one of the requirements under classical Dow Theory for a secondary reaction to exist) and merely requiring a 3% move, many movements that under classical Dow Theory escape the definition of secondary reaction are labeled as such under Schannep’s Dow Theory.

Thus, the very make up of Schannep’s Dow Theory makes it foreseeable that in the future it will continue to cut losses short (that is detecting earlier changes of the primary trend) because its very rules are designed to spot secondary reactions in an early fashion.

Of course, critics could say that everything comes at a price, and that premature labeling of secondary reactions makes Schannep’s Dow Theory prone to false signals or worse yet, reduced profits.

However, such objections have been exhaustively debunked during this “face off” saga. Schannep’s rules, while being “early” both in signaling entries and exits, manages to increase profits, not reduce them.

So for a long-term investor (long term being for me trades lasting on average one year or more) Schannep’s Dow Theory is the closest thing to the holy grail. Losses are greatly diminished while profits are increased.

Sincerely,

Manuel Blay

Editor of thedowtheory.com