Foretelling stock market tops is the hardest part of market timing. There are some excellent “pre-BUY” indicators which come in around market bottoms as discussed in “The COMPOSITE Timing Indicator”, but very little in the way of an advance indicator for market tops. There is, however, something about the yield curve that can be very helpful in that regard.

Long-term interest rates are usually higher than short-term rates, the simple explanation being that long-term lenders demand a premium to compensate for expected probable inflation, whereas short-term rates don’t usually face that prospect. Sometimes that relationship is reversed due to a combination of factors not easily explained: perhaps the Federal Reserve Board has increased short-term rates to slow an over-exuberant economy and long-term holders expect them to be successful and therefore not demand any premium. Or the Fed is trying to offset potential inflation and long-term holders don’t see inflation as a threat. There are other possible reasons, but the fact is it happens, and when it does it is described as an inverted yield curve. The actual definition varies from:

| The yield on 3 month treasury bills: | versus the: | 10 year notes (N.Y.Fed.Res 6/96) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 months | vrs | 20 year bonds (Forbes 1/23/89) |

| 3 months | vrs | 30 year (Wall St. Journal 2/13/89) |

| 1 year notes | vrs a composite | over 10 years (Forbes 3/27/95) |

| 2 year | vrs | 30 year (TheStreet.com 1/27/00) |

| 5 to 10 year | vrs | 30 year (Wall St. Journal 1/28/00) |

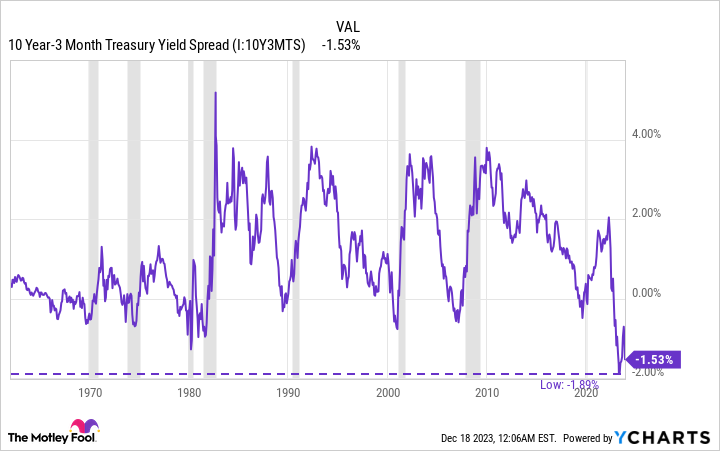

My work shows that the relationship between the 3 month and 10 year is the most useful, as does that of the New York Federal Reserve Bank as shown below. The 10 year Treasurys have become the benchmark of the bond market. Whichever definition you choose, the after-results of a flattening to inverted yield curve are the same: a slowing economy at best, and a depression at worst, but usually a recession.

I recommend a 1996 study by the N. Y. Federal Reserve Bank covering the previous 35 years as an excellent background piece on this subject (after clicking on ‘study’ return by the ‘Back’ button on your browser). Their ‘Estimated Recession Probabilities for Probit Model Using the Yield Curve Spread” (Four Quarters Ahead, using the spread between the interest rates on the ten-year Treasury note and the three-month Treasury bill) are:

Recession Probability (Percent) Value of Spread (Percentage Points)

10 0.76

15 0.46

20 0.22

25 0.02

30 -0.17

40 -0.50

50 -0.82

60 -1.13

70 -1.46

80 -1.85

90 -2.40

Toward the end of the year 2000 the spread approached a negative -0.90 points, implying over a 50% chance of recession, up from a just a 10% chance at the start of 2000. And, of course a recession DID occur from March 2001 through November 2001.

A February 2006 Federal Reserve working paper on “The Yield Curve and Predicting Recessions” updated the earlier study and concluded that chances of recession are lower if Fed Funds rates are low and higher if they are high. The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee sets the target interest rate for the Fed Funds rates and they are usually similar to the 3 month Treasury note yield. The point of the update was to prove that the economy works better in a low interest rate environment and recessions are more likely when interest rates are high.

In March 2006, the 3 month Treasury note average rate was 4.51% and the 10 year Treasury bond rate was 4.72%. Using that 0.21 spread between the two when Fed Funds are at a 3.5% level would put the chances of recession at 17% as opposed to the 20% shown above. Alternately, if Fed Funds are 5.5% and the spread is the same 0.21% then the chances double to 35%. This ‘new’ information seems to endorse the approach I have used for many years as you will see below.

My work encompasses the past 65 years from 1953 to the present and uses the monthly average three-month Treasury bill rate divided by the monthly average ten-year Treasury bond yield. The data can be found at http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/data/TB3MS.txt and http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/data/GS10.txt. It is evident that as the ratio reaches or exceeds 0.95% (the rate on the short-term bill approaches the level of the long-term bond), the economy drops into a recession*.

It is clear that there has been a relationship that has been in effect for at least the last 100 + years! In 2001 the ratio not only exceeded 0.95%, but the 3 month yield exceeded the 10 year yield by a considerable amount. The recession lasted from March through November that year. In early and mid-2006 it once again exceeded 0.95%, and in late 2006 and early 2007 the 3 month yield exceeded the 10 year yield, so obviously I expected an economic slowdown and/or recession in the year ahead, not in 2006 but likely in late 2007 or 2008. Note: NBER later selected 12/07 as the start.

Think there’ll never be another recession? History doesn’t support that conclusion.

Here are the results of flattening or Inverted Yield Curves over the last 100+ years:

| Approximate (month/year) | Months | Stock Market | Bear | Months | Recessions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start: | End: | Lead to: | High: | Low: | Decline (DJIA) | Lead_to | Start: | End: |

| Jun-1900 | Mar-03 | 12 mos. | Jun-1901 | Nov-03 | 46% | 27 | Sep-1902 | Aug-04 |

| Jul-04 | Jun-08 | 18 | Jan-06 | Nov-07 | 49 | 34 | May-07 | Jun-08 |

| Jan-10 | Jun-10 | -2 | Nov-09 | Sep-11 | 27 | 0 | Jan-10 | Jan-12 |

| Jul-12 | Jun-13 | 2 | Sep-12 | Jul-14 | 25 | 6 | Jan-13 | Dec-14 |

| Jun-18 | Dec-20 | 17 | Nov-19 | Aug-21 | 47 | 2 | Aug-18 | Mar-19 |

| May-27 | Apr-29 | 28 | Sep-29 | Jul-32 | 89 | 27 | Aug-29 | Mar-33 |

| Feb-57** | Mar-57 | -10 | Apr-56 | Oct-57 | 19 | 6 | Aug-57 | Apr-58 |

| Dec-59 | Jan-60 | 1 | Jan-60 | Oct-60 | 17*** | 4 | Apr-60 | Feb-61 |

| Jan-66 | Mar-67 | 1 | Feb-66 | Oct-66 | 25 | 11 | Dec-66* | Jun-67 |

| Apr-68 | Apr-70 | 8 | Dec-68 | May-70 | 36 | 20 | Dec-69 | Nov-70 |

| Jun-73 | Jan-75 | -5 | Jan-73 | Dec-74 | 45 | 5 | Nov-73 | Mar-75 |

| Nov-78 | May-80 | -2 | Sep-78 | Apr-80 | 16 | 14 | Jan-80 | Jul-80 |

| Oct-80** | Oct-81 | 6 | Apr-81 | Aug-82 | 24 | 9 | Jul-81 | Nov-82 |

| Apr-89 | Jan-90 | 15 | Jul-90 | Oct-90 | 21 | 15 | Jul-90 | Mar-91 |

| Sep-98 | Jan-99 | -2 | Jul-98 | Aug-98 | 19 | 30 | Mar-01 | Nov-01 |

| July-00 | Mar-01 | -6 | Jan-00 | Sep-01 | 30 | 8 | Mar-01 | Nov-01 |

| Jan-06 | Apr-06 | 21 | Oct-07 | Nov-08 | 47 | 23 | Dec-07 | Jul-09 |

| also July-06 | Jul-07 | 15 | Oct-07 | Nov-08 | 47 | 17 | Dec-07 | Jul-09 |

| May-19 | Nov-19 | 9 | Feb-20 | Mar-20 | 37 | 9 | Feb-20 | Apr-20 |

| also Feb-20 | Mar-20 | 0 | Feb-20 | Mar-20 | 37 | 0 | Feb-20 | Apr-20 |

| Oct-22 | Dec-24 | 26 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Feb-25 | ?? | |||||||

Average lead: 6.3 mos. to Bear market

Average lead: 13.6 mos. to recession

*counting the officially designated recessions and the 1967 ‘growth recession’ per Forbes (1/23/89) when industrial production fell from the 1st quarter to the 3rd.

**also 12/57 during the recession, and 2/82 during that recession

***Correction only (S&P500 did not drop 16%).

The BOTTOM LINE: A flattening or inverted yield curve points to a Bear market and a coming recession. It usually leads a bear market starting by some 6 months on average, but in 1/3rd of the previous occurrences a Bear market had already started, although none were yet defined or recognized by the date of the flattening or inversion shown. The lead time prior to the onset of a recession has been just over a year on average, and in 19 out of the 20 (95%) flattenings/inversions an official recession has followed. It is a far better predictor than are Bear markets which usually are followed by recession (17 of 22 or 77% in the 20th century were). A weekly graph of the Treasury yields is available at http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/. As the Federal Reserve Bank of N.Y. says: “forecasting with the yield curve has the distinct advantage of being quick and simple”, so you can keep an eye on it yourself. Of course we will be watching it for you and reporting on it in these Letters when it is appropriate.